Hardcoded Credentials in Uniguest Kiosk Software lead to API Compromise

If you’ve traveled at all within North America, you’ve likely at some point noticed or even used the shared kiosk machines available in hotel lobbies. These are typically running a locked down version of Windows, and chances are they are managed by Uniguest software.

Uniguest kiosk software will restrict the user to simple tasks, such as maybe browsing the web or printing boarding passes. Uniguest software can be found in other industries, not just hospitality:

“Uniguest is the global leader in providing highly secure, fully managed customer-facing technology solutions on an outsourced basis to the hospitality, senior living, specialty retail, education and corporate sectors. Our suite of turnkey consumer-facing technology solutions includes hardware and software solution packages, system implementation, and 24/7/365 multi-lingual support for public space kiosks, purpose-built kiosks (PC, iMac, tablet), digital signs, tablets, remote printing and more – all designed to deliver a consistent and safe experience to our clients’ customers.”

Based on the way their infrastructure setup, it appears Uniguest actually manages the machines and not the hotel or whatever other business employs Uniguest software.

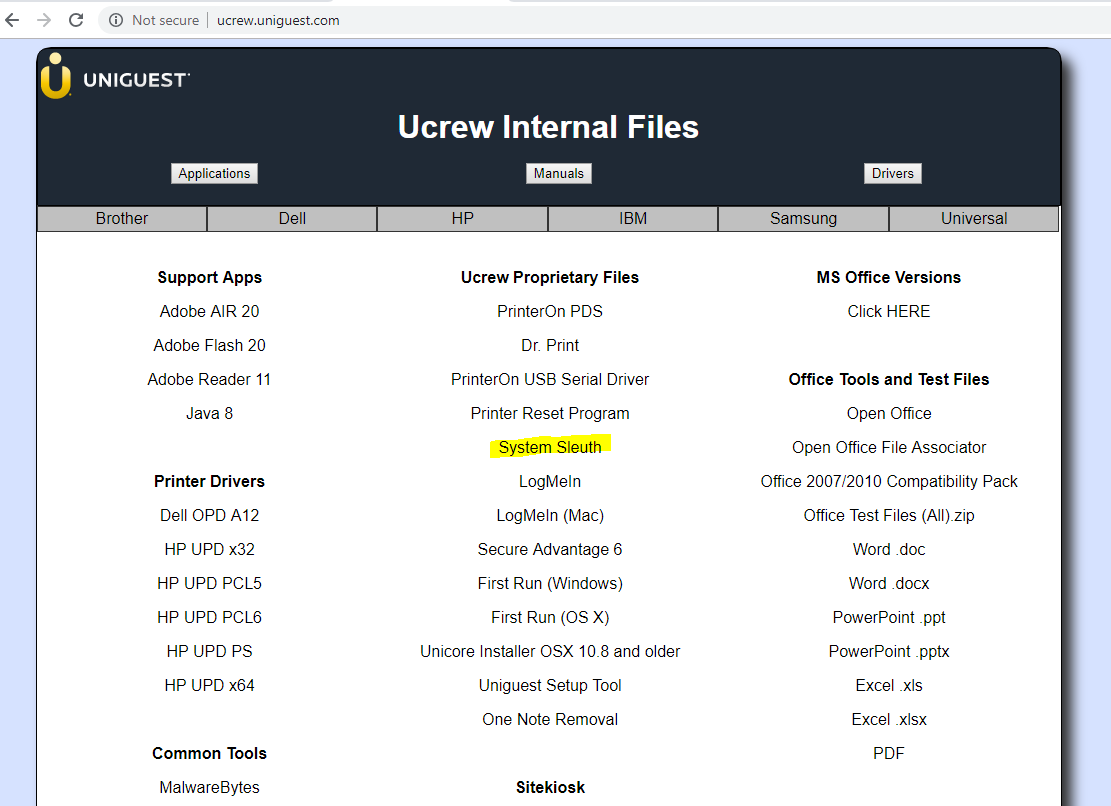

With a quick Google search, I noticed that Uniguest had exposed a website publically (ucrew.uniguest.com) which appeared to contain all the tools their technicians would need to deploy or manage a kiosk on location:

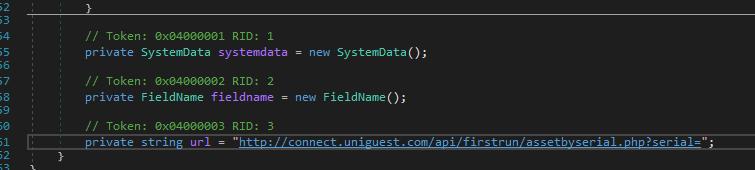

There was no authentication required, and among the pre-packaged kiosk software and manuals, SystemSleuth stood out. SystemSleuth is written in C# and is therefore trivially decompiled back to source code using something like dnSpy.

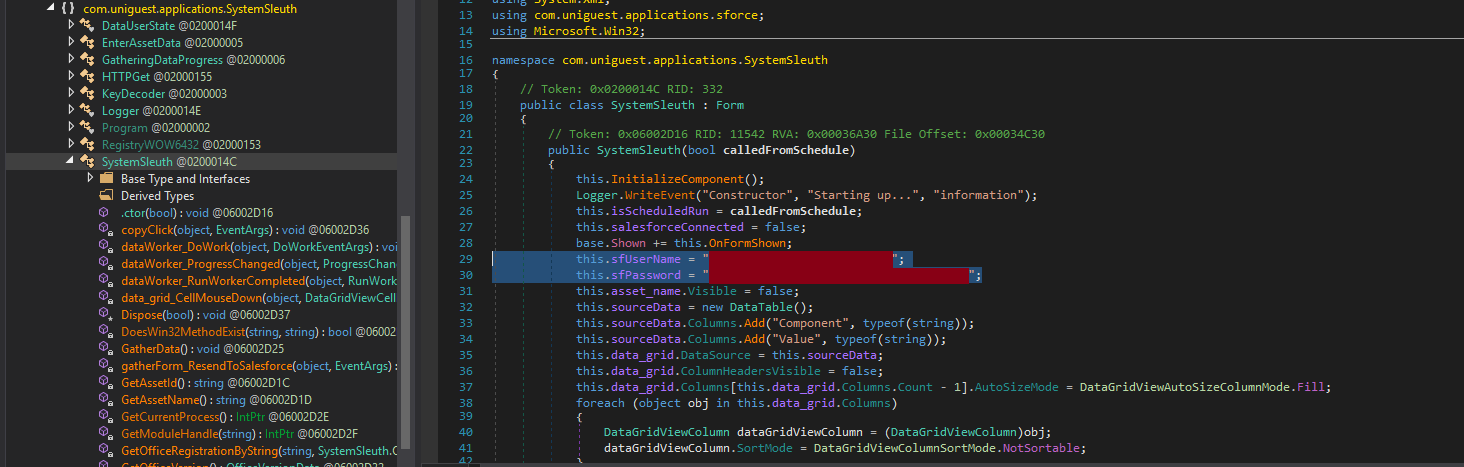

Static Analysis

SystemSleuth is an application that is deployed to all of their kiosks and its purpose appears to be the collection of kiosk (asset) information such as product keys, asset tags, passwords and various other data. The data is sent up to a Salesforce API and of course, with the C# decompiler, it didn’t take long to find the API credentials, hardcoded within the application:

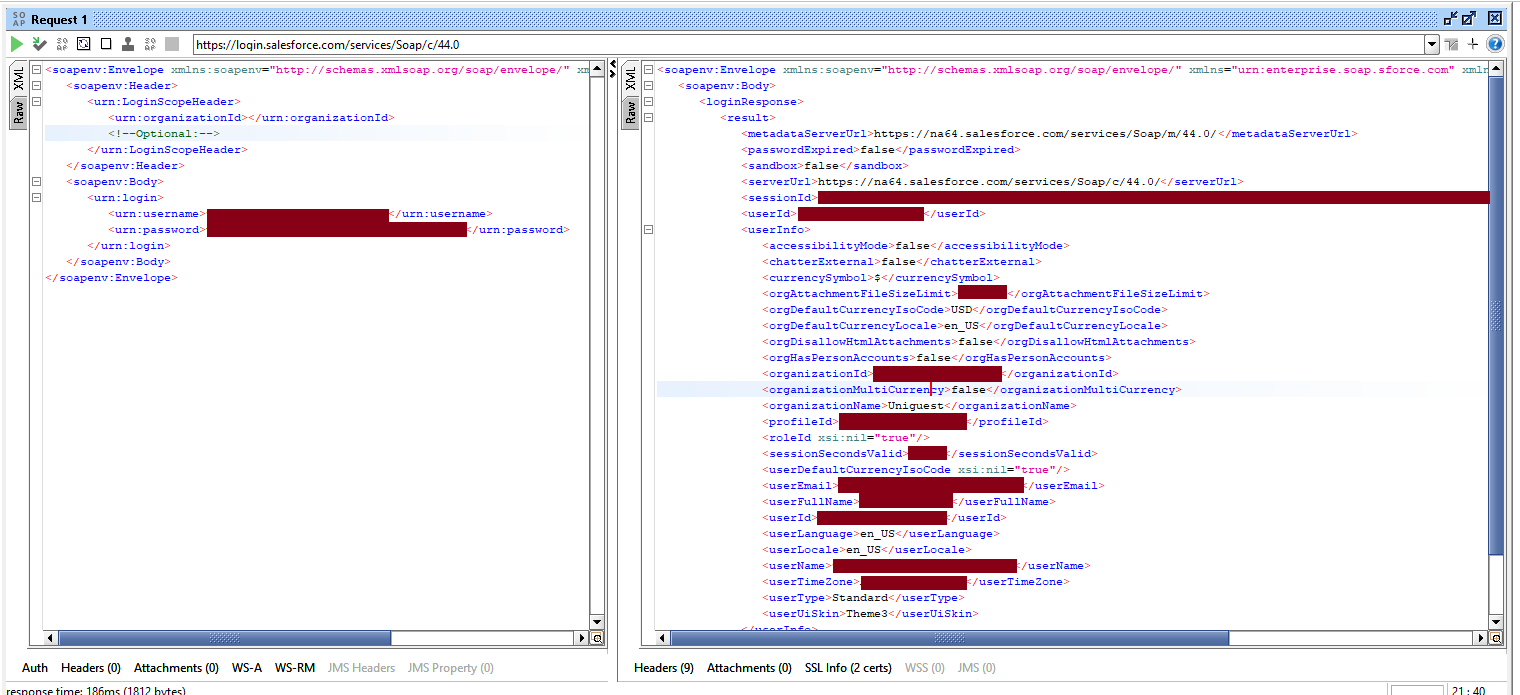

The Salesforce API is accessible via the SOAP protocol and we can use the open source SoapUI tool to run some test queries.

First we need a session ID issued by authenticating to the Salesforce SOAP API. The server responds with a session key which we can use in subsequent requests:

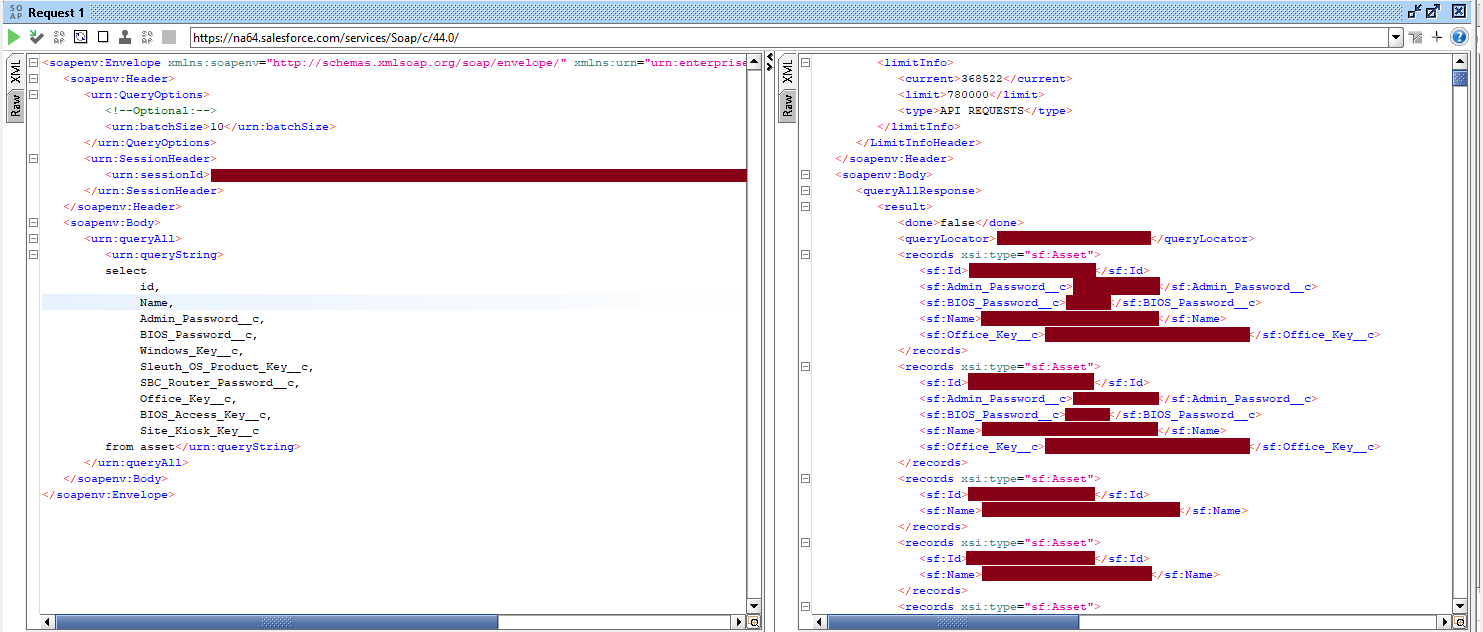

We can now dump all the data in the Uniguest cloud database, which includes admin, router and BIOS passwords, product keys and various other sensitive information, for what looked like all of Uniguest’s customers.

With this information in hand, adversaries could deploy keyloggers, remote access trojans and various other forms of malware, attacking hotel guests or business patrons just passing through.

Uniguest has been contacted and have since placed the ucrew.uniguest.com site behind an authentication portal, but it’s important to remember that SystemSleuth and the API credentials (albeit disabled) may still be found on their managed systems, until Uniguest can go and reimage them all.

Locking down a Windows machine enough that it can be trusted in a public setting such as a hotel lobby, is a daunting task. Restrictions imposed by Active Directory Group Policy Objects (AD GPOs) or custom Explorer shells are often trivial to bypass, giving attackers access to the whole system.

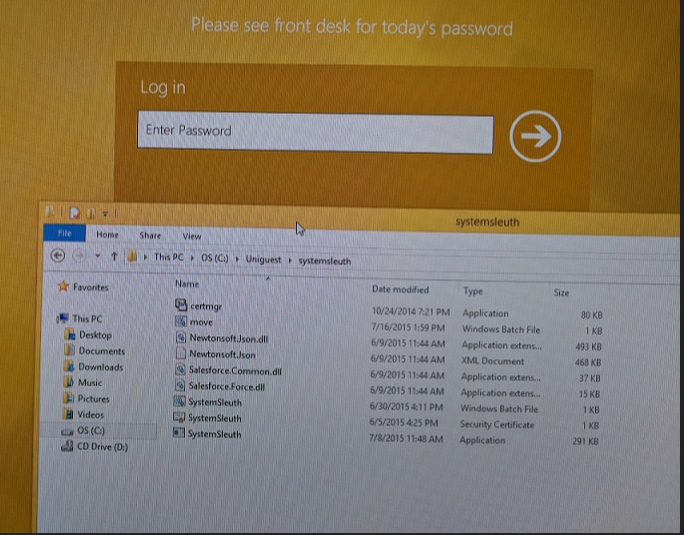

The following is an example of a successful sandbox escape in one of Uniguest’s kiosks, revealing SystemSleuth.exe on the disk, ready to be exfiltrated and analyzed:

Additional Findings

Following responsible disclosure policies, these issues were reported to Uniguest who was quick in their response. However after I went back to verify their fixes, I found more issues.

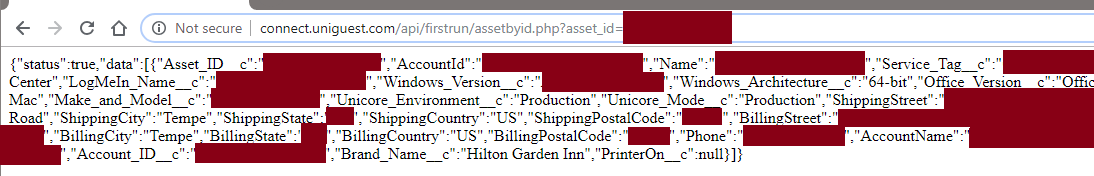

An older version of the SystemSleuth binary had referenced another account for the Salesforce API and also contained a reference to an open API used to gather asset inventory data. Both of these were still functional.

The assetbyid.php tool (http://connect.uniguest.com/api/firstrun/assetbyid.php) also exists and allows query by asset ID. Serial or Asset ID may be printed on the kiosk and could also be somewhere in the system info (hostname, or system data stored in WMI). These values could also be guessed through bruteforcing, but may be more difficult to do without some knowledge of how the values are generated.

An unauthenticated GET request to this open API using an asset ID returns information to the public:

Lessons Learned

If you’re thinking about using a SystemSleuth-like application in your deployments, don’t, but if you insist, consider the following tweaks:

- Use a write-only API key

- Deploy per-customer databases

- Do NOT reuse API keys or credentials between customer deployments

Developers may consider a code obfuscator for .NET like ConfuserEx in an attempt to secure their C# binary. I advise against this move as it does not stop attackers, but merely slow them down. Sometimes not even by that much.

I should also note that while the amazing dnSpy made analysis a breeze in this instance, hardcoding credentials in a native C++ application would lead to the same outcome. Obfuscating source code or the binary would not stop a determined attacker.

For most threat models, The best solution is to never hardcode sensitive information in applications. but, of course, your situation may be different.

A potential alternative to SystemSleuth and the API is to manage these assets using something like Microsoft’s Intune and segregating these environments on a per-customer basis.

Intune has a Kiosk feature, which may work better than custom GPOs and Explorer shells.

There are certainly more secure ways to manage Windows assets, but they may come at an increased cost to businesses. The simple answer is to dispose of applications like SystemSleuth and the Salesforce API. This may sound like an expensive endeavor but a compromise of all client data and machines could be much more impactful to the bottom-line than any IT project.

Disclosure Process

Uniguest worked closely with the us throughout the process both during the first findings and with the second round of findings. They’ve remediated the issues by deprecating the SystemSleuth application as well as removing access to the embedded credentials, however they do not believe the open “Connect” API is a vulnerability.

All software has vulnerabilities to a greater or lesser degree. A good judge of the security posture of any vendor is not if there are vulnerabilities are found in their products, but how quickly and seriously the vendor addresses those vulnerabilities. It will come as no surprise for anyone that has worked with responsible disclosure that many vendors respond to vulnerability notifications from third party researchers with either silence or with even open hostility. Compared to other vendors Uniguest was a pleasure to work with during the disclosure process. They took the reports seriously, worked hard to address the issues on legacy products and had have taken steps like incorporating application and physical penetration testing to their product development lifecycle.

Disclosure timeline

- 2019-01-09 - Issue disclosed to Uniguest

- 2019-02-08 - Uniguest investigates the issue internally

- 2019-03-27 - Uniguest confirms remediation

- 2019-04-11 - Additional findings reported to Uniguest

- 2019-04-30 - Additional issues confirmed to still be present

- 2019-06-11 - Uniguest responds to the additional findings, fixing one and leaving the open API accessible

- 2019-07-11 - Published